In recent years, the Balkan region has witnessed a notable shift towards aligning with liberal values, marking a significant departure from its historical narrative. The convergence of liberal principles, encompassing democratic governance, human rights, and free-market economies, has become a focal point in the geopolitical landscape of the Balkans. However, political and economic integration between the Western Balkans and Europe is delicate. It compels us to raise certain questions. What are the prospects for closer ties with the European Union and its values? What initiatives are being taken in this direction, and who are the major actors driving them? This writing aims to provide insights that shed light on the dynamics between the European Union and the Western Balkans on both economic and social levels. To do so, Considering the power of states through their financial resources, our first focus will be on the political and economic support of European governments in the Western Balkans. Then, we will briefly discuss the institutional and ideological obstacles encountered and finally conclude by underlining the importance of both multi-governmental organizations and non-state actors in the region.

The Berlin Process

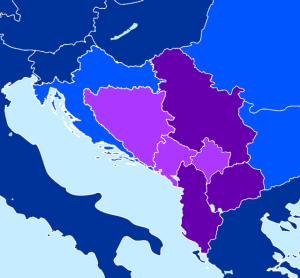

On Wednesday, December 13, 2023, the EU-Western Balkans summit took place in Tirana. Since 2014, annual summits have been held to promote EU values within Southeastern European countries. The initiative, known as the ‘Berlin Process’, was initially proposed by Germany with the aim of ensuring peace, security, and stability in the Western Balkans, while also supporting the region’s development. The Berlin Process emerges as a glimmer of hope more than 10 years after the unfulfilled promises of Thessaloniki, initiated by Athens in the wake of the Greek presidency of the European Union in the second half of 2002. It fosters improved cooperation opportunities among the Western Balkan countries: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia. While all six countries aspire to join the EU, they are at different stages of the accession process. Currently, the EU is in negotiations for accession with Serbia, North Macedonia, Montenegro, and Albania. Bosnia and Herzegovina is considered a candidate for accession, while Kosovo is a potential candidate for EU accession.

CEFTA / ALECE as a gateway to the European Union

The Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA), known in French as Accord de libre-échange centre-européen (ALECE), is an economic agreement among Southeast European nations. Originally designed as an economic complement to the Visegrad Group, CEFTA serves as a steppingstone toward integration with the EU and NATO. Established in 1992, it underwent several expansions until 2007, but also experienced a reduction in membership in 2004 and 2007 when certain countries joined the European Union. This led to a shift in the geographical scope of CEFTA towards Southeast Europe. The free trade agreement is integrated into the Stabilisation and Association Agreements (SAAs) between the European Union and certain Western Balkans countries.

The revival of Open Balkan ?

The idea of the Open Balkan came in the early 1990s. The Open Balkan is an economic and political zone of Albania, North Macedonia and Serbia. With the establishment of the zone, all three member states aim to increase trade and cooperation as well as improve bilateral relations.

Formerly known as Mini-Schengen Area, the project was launched on October 10, 2019, in Novi Sad and took the name Open Balkans on July 29, 2021. It is criticized and perceived by some as a ‘Greater Serbian’ project. The project gradually lost its initial enthusiasm, and the health crisis almost rendered it obsolete. However, Open Balkan is now indirectly brought back to the table due to the April 2023 election of the new president of Montenegro, Jakov Milatović. According to the new president, who has the support of the 27, the future of the Western Balkans depends on regional economic collaboration, whether through CEFTA or any other reconciliation process. But given the challenges facing the region, some pessimistic voices within the EU believe that Open Balkan could be an alternative to the European Union.

EU strategy

Just as some European sanctions against Moscow strengthen Russia’s independence, the Russian invasion of Ukraine revives European unity and even encourages its expansion. The war has abruptly brought enlargement to the top of the agenda. A shake-up that prompted Brussels to redouble efforts to accelerate the enlargement process. The latest major development regarding the EU expansion in the Western Balkans is Bosnia and Herzegovina officially obtaining candidate status on December 15, 2023.

This results also in significant funding for the region. In November 2023 for example, the Commission presented a new Growth Plan for the Western Balkans. Between 2024 and 2027, the European Commission is suggesting a financial package comprising €2 billion in grants and €4 billion in loans with favorable terms. Additionally, the proposal outlines a step-by-step assimilation of the Western Balkan nations into seven vital sectors of the EU single market. These sectors include the free movement of goods, services and workers, the Single Payment Area (SEPA), the energy and digital markets, road traffic and industry. Furthermore, the plan aims to expedite the establishment of a unified regional market in the Balkans, with the potential to generate 10% economic growth, as indicated by the Commission.

Is financial support sufficient?

The path seems lengthy. Dušan Reljić, the former head of the Brussels office of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP), views the European Commission’s latest plan as favorable. However, he believes it won’t significantly propel the growth of the Western Balkans. According to his assessments, achieving an annual growth rate of 6 to 8% is necessary for these candidate countries to reach the EU average within the next three decades.

Economic integration would be abrupt due to the imbalance between the EU and the Western Balkans as well as the weakness of economic convergence. The model of economic relations between the EU and the region is unfavorable to the Balkan countries and limits growth. The opening of these countries to the European market has increased their trade deficit by almost €100 billion over the last 10 years. Imports from the EU exceed exports, and this trend will only intensify with a deepened market opening without real structural change. That is why an initial development among these countries is an intriguing idea within the European strategy, facilitated by the Berlin Process. The improvement of regional cooperation should prevail.

However, the EU’s financial strategy follows a simple classic neoliberal logic and does not seem to respond to the extraordinary geopolitical events we are currently experiencing. The history of Eastern Europe has taught us many lessons. Injecting funds does not seem to be the solution. Without a strong and stable institutional framework that establishes the rule of law, the positive effects of EU financial assistance would remain limited, and the funds even could be hijacked by bribery practices. This critique does not imply that the financial strategy has no impact. As a matter of fact, it remains a significant support and a political message that can have its long term effects. The European Commission will not turn away from the Western Balkans despite the geopolitical situation. It will not diminish its emphasis on the rule of law, values, and alignment with its foreign policy either.

Political and nationalist divisions

The Yugoslav constitutional reforms of 1974 granted the same rights as other constituent parts of the federation to Vojvodina and Kosovo. Serbia, which considered these entities as its provinces, felt humiliated and politically weakened within the Federation. From 1980 onwards, following the death of Josip Broz Tito and economic challenges, long-standing resentments among different populations, previously contained, resurfaced. Through a relative liberalization of the media and the expression of intellectuals, there was a resurgence of nationalist discourse. On both the Serbian and Croatian sides for example, there was a belief that the other was in a dominant position, violating the rights, and denying the identity of its counterpart. The rise of Slobodan Milošević to power in Serbia in 1987 and the fall of the Berlin Wall two years later created conducive conditions for the escalation of violence in the region.

The ensuing wars established violence and hatred, making it impossible to entertain a different perspective on regional issues. In Bosnia, for example, the ethno-nationalist system of the Dayton Accords signed in 1995 permanently entrenched this vision. The press and the international community adopted the language and arguments of ethno-nationalists’ parties, perpetuating the myth of uniform community groups, where each member is supposed to think the same way as everyone else. By eliminating differences, divergences, and the fluidity of social identities, the existence of theoretical homogeneity was validated, as if being Serbian, Croatian, or Bosnian was not possible without also being Bosniak, atheist, communist, or anti-nationalist.

Similar to how European integration was an effective means to counter nationalism, the idea of Balkan integration is perceived as an instrument capable of containing nationalism in the region. However, this project faces reality on the ground. This is particularly evident when observing the harmful impact of political issues on the regional development of trade. According to Dejan Jovović, former scientific advisor to the federal government of the Union of Serbia and Montenegro, “the Balkans are still far from constituting a single market.” The CEFTA Secretariat has identified over a hundred obstacles hindering free trade in the region. As per the former advisor, the main reasons are primarily political, even though the lack of complementarity in economies also represents an undeniable obstacle to the growth of exchanges. While CEFTA initially brought a breath of fresh air to the region, the political sphere gradually interfered increasingly in its economic functioning, particularly during electoral periods. Politicians erect barriers, justifying this by protecting their economic interests or gaining political points with their voters.

Institutional framework

The recent European Commission country reports highlight critical issues in the Western Balkans, including a limited number of convictions involving high-ranking officials, selective judicial follow-up, political interference, and challenges in implementing anti-corruption legislation. The reports also emphasize significant delays in adopting crucial legislative measures, such as laws on anti-corruption agencies and strategies, which impede the effectiveness of anti-corruption efforts across the region. While there has been progress through specialized agencies, concerns persist about corruption infiltrating state structures, particularly within the judiciary and law enforcement at high levels in every Western Balkan country. Legal penalties for corruption-related offenses and delays in high-profile cases undermine the overall impact of anti-corruption initiatives.

Within a liberal system, states provide the institutional framework within which civil society operates. Therefore, it is necessary to emphasize that non-governmental actors are equally important as states in the process of liberalization, both economically and socially. After all, they largely constitute the individuals of society. The success of institutional reforms often depends on the collaboration and commitment of various actors, both at the national and international levels. It includes the participation of international organizations such as the OSCE but also civil society through certain NGOs active in the region, experts and researchers from various universities providing analyses and studies, and the media playing a role in raising awareness of liberal values.

Before concluding this writing, it is important to mention a crucial aspect regarding the approach with which all these actors try to instill certain liberal values. Sometimes, the issue may be addressed by Westerners in a paternalistic or even condescending manner. As a former unique communist country, Western Balkans and its inhabitants have been perceived as apathetic since the end of the war. They should be educated about participatory democracy and multicultural tolerance, which, presumably, they are unfamiliar with. Thinking this way, we neglect 45 years of self-management socialism, factory committees, workers’ plenums, and intensive unionization within a multicultural society. An ignorant perspective encourages a patronizing approach to the issue and can even lead to a loss of trust.

The events currently unfolding in Eastern Europe are highly interesting and will significantly impact the dynamics of relations between the Western Balkans and the European Union. It is crucial for Europe not to overlook what is happening in the Balkans. It is imperative to pay attention to this region not only because it is in Europe but also because it is a crossroads of diverse cultures that are, sometimes wrongly, perceived as too foreign to European values. If Western nations fail to grasp the complexities of their own territory, they lose a considerable asset and a chance to wield greater influence in international relations.

Sources:

Pictures : Canva Pro; Wikimedia Commons

- Central European Free Trade Agreement. Link: HYPERLINK “https://cefta.int/”https://cefta.int/

- Dérens Jean-Arnault et Catherine Samary. « Dayton », , Les 100 Portes des Conflits Yougoslaves. sous la direction de Dérens Jean-Arnault, Samary Catherine. Éditions de l’Atelier, 2000, pp. 97-102.

- DonnéesMondiales.com. Link: HYPERLINK “https://www.donneesmondiales.com/accords-commerciaux/alece-accord-de-libre-echange.php”..

- European Commission: European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations (DG NEAR). Link: https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/news/commission-presents-new-growth-plan-western-balkans-including-eu6-billion-grants-and-loans-2023-11-08_en

- European Parliament. Facts Sheets on the European Union. Link: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/fr/sheet/168/the-western-balkans

- European Commission’s Countries Reports. Link: https://commission.europa.eu/business-economy-euro/economic-and-fiscal-policy-coordination/european-semester/european-semester-timeline/spring-package_en

- Sokic, Alexandre. « ALECE et Balkans occidentaux. Entre intégration régionale et intégration européenne », Le Courrier des pays de l’Est, vol. 1063, no. 5, 2007, pp. 44-52.

- SRF, Deutschland und Slowenien streben EU-Erweiterung an, 05.12.2023. Link: https://www.srf.ch/news/international/westbalkan-laender-deutschland-und-slowenien-streben-eu-erweiterung-an

- L’ECHO, « Un plan de 6 milliards d’euros pour stimuler l’élargissement de l’Union européenne ». Link: https://www.lecho.be/economie-politique/europe/general/un-plan-de-6-milliards-d-euros-pour-stimuler-l-elargissement-de-l-union-europeenne/10504939.html

- Jean-Baptiste Chastand, « Nouvelle donne pour le processus d’intégration des Balkans occidentaux à l’Union européenne ». Link: https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2023/09/17/nouvelle-donne-pour-le-processus-d-integration-des-balkans-occidentaux-a-l-union-europeenne_6189735_3210.html

- Milica Starinac, European Western Balkans, « EC 2022 Reports on the Western Balkans: Track record on fighting corruption needs to improve ». 14.10.2023.

- Simon Rico, Le Courrier des Balkans, « Les soldats Rama et Vučić bien seuls pour défendre Open Balkans », 23.05.2022.

- La rédaction, Le Courrier des Balkans, « Edi Rama annonce la fin d’Open Balkans et entame une tournée régionale ». 6.07.2023.