More than a decade has passed since a young street vendor set himself on fire in Tunisia, triggering the Arab Spring. Since then, the people have toppled leaders, started revolutions, and forced reforms – but how far have Middle Eastern democracies actually come?

Academia has theorized that Arab or Muslim “exceptionalism” is at the root of slow democratization in the region. Historically, theoreticians and observers have viewed the region mostly through a wholly state-centric lens, based on a different understanding of the traditions and practices of states. As a result, most theories were developed for the Middle East, but not by the Middle East.

Yet, it is important to understand the particular conditions under which these states have developed. Much of the Western media recurringly blame slow democratization – especially in the Levant – on its divided societies. And yet, we seem to conveniently forget the role that foreign powers played, especially Western diplomats, in fueling regional instability.

In this multi-part series, we’ll see how diplomacy has impacted regional stability, democracy and self-determination in the Levant. In this first part, we’ll set the stage by exploring how European diplomats divided the Levant at the beginning of the 20th century, creating the nation-states on the map today. In further articles, we’ll look at concrete examples of how this still impacts democratization in the Levant today.

How the Levant was divided

Especially in the Levant, the arbitrary and artificial nature of the created nation-states severely impacted the subsequent inclusivity of various ethnic groups in political processes.

Historically an arid territory of trading cities and nomadic tribes, Levantine people identified most strongly with sub-state units – cities, tribes, religious sects – or the supra-state umma (meaning the community of believers of Islam). Yet, despite these varying identities, there was a vision of order: “of peoples cohabiting in a relatively seamless space, of tolerance and diversity – cultural, linguistic and religious”. [1]

By the end of the sixteenth century, the Ottomans had built the largest and most powerful empire in the Muslim world. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, however, the Ottoman Empire experienced major military defeats at the hands of European powers. Consequently, it was pressured into implementing various “reform” programs that would open its population and resources to European exploitation.

Istanbul’s modernizing elite was originally intent on building a highly centralized system and efficient governance that might one day rid the Empire of European hegemony. Instead, the European pressure that had reached “all-intrusive levels short of direct conquest and colonization” forced the Empire to its knees.

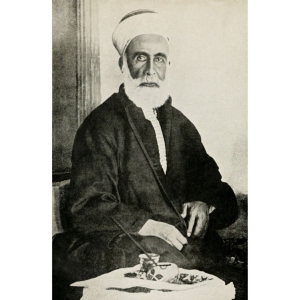

For the final coup de grâce, however, Europeans needed Arab support. As World War I neared its end, they turned to Sharif Husain, ruler of Mecca, descendant of the Prophet Muhammad and leader of the underground Arab nationalist movement. In the famous “Husain-McMahon letters”, European diplomats promised the Sharif Arab independence – in the form of an Arab state – in exchange for his support in overthrowing the Ottoman Empire.

For the final coup de grâce, however, Europeans needed Arab support. As World War I neared its end, they turned to Sharif Husain, ruler of Mecca, descendant of the Prophet Muhammad and leader of the underground Arab nationalist movement. In the famous “Husain-McMahon letters”, European diplomats promised the Sharif Arab independence – in the form of an Arab state – in exchange for his support in overthrowing the Ottoman Empire.

Unbeknownst to Husain, however, European powers had no intention of keeping their promise of the Arab state, calling it an “absurdity” on account of Arabs being “a heap of scattered tribes with no cohesion and no organization.” [2] Instead – once Husain’s Rebellion (“the Great Arab Revolt”) had pushed the Ottoman Empire out of the way – European rulers divided the Arab provinces among themselves in a series of agreements and declarations (the most important ones being the Constantinople Agreement of 1915, the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 and the Saint-Jean de Maurienne Agreement of 1917).

Why it matters

The borders of these new colonies and mandates cut across pre-existing boundaries and identities. Though arbitrary, these same borders were maintained in the subsequent imposition under Western imperialism of a “deeply flawed version of the Western states system”. While the nation-states in the Levant were created early after WWI, they long remained under British and French rule and only gained independence in the 1930s and 1940s.

As Ayubi states in his landmark study on the state formations in the greater Middle East, the primary concern in the creation of states in the Middle East was not how the diverse ties – whether cultural, ethnic, or religious – formed administrative units in the new state. Instead, the founders formulated the state to be “a unit of control for masking the diversity of the population and subduing its cultural, linguistic and religious heterogeneity under command structures.” In other words, states were formatted to control their subjects and their borders were drawn regardless of or even against indigenous wishes and took uneven account of pre-existing boundaries and identities.

To summarize, European diplomats have played a large role in the demographic make-up of many states in the Levant. The fact that the state system in the Levant is built on a history of imperialism, colonialism, hegemony and – in Arab public perception – treason, still has profound consequences on domestic and regional political processes in the region today.

In the next parts of this series, we’ll explore concrete examples of how consequential and long-lasting choices made by foreign diplomats– even 100 years later – can be on regional stability and democratization efforts.

Sources:

[1] Louise Fawcett, “Introduction: The Middle East and International Relations” in International Relations of the Middle East 5 th Ed., Louise Fawcett, ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019): 7.

[2] James Barr, “Monsieur Picot” in A Line in the Sand. Britain, France and the Struggle for the Mastery of the Middle East (London: Simon & Schuster, 2011): 29.

Henry McMahon and Hussein bin Ali, Correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon, G.C.M.G., His Majesty’s High Commissioner at. Cairo and the Sherif Hussein of Mecca, July 1915 – March 1916, published in 1939 as Cmd. 5957.

James Barr, “Monsieur Picot” in A Line in the Sand. Britain, France and the Struggle for the Mastery of the Middle East (London: Simon & Schuster, 2011): 29.

Louise Fawcett, “Introduction: The Middle East and International Relations” in International Relations of the Middle East 5 th Ed., Louise Fawcett, ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019): 7.

Raymond Hinnebusch, “The Politics of Identity in Middle East International Relations” in International Relations of the Middle East 5 th Ed., Louise Fawcett, ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019): 159-160.

Wael B. Hallaq, An Introduction to Islamic Law (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009): 93-94, 103.